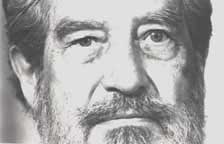

OCTAVIO PAZ:

THE POET IN HIS LABYRINTH

by Homero Aridjis

One autumn afternoon in 1963, I met Octavio Paz for the first time, in Mexico City. He was en route from Paris, where he had been in the Mexican foreign service, to India, where he had been appointed ambassador. Strolling between the lofty trees along the Paseo de la Reforma, he said he was going to India because he had no other alternatives for work in Mexico, even though the Asian nation little sparked his interest because he was himself from another exotic country.

These personal

revelations surprised me because they told much about him. His first

sentence expressed the feeling that he was insufficiently loved in his

own country, a sentiment I feel he carried with him to the end of his

days. The second sentence showed that he was far from foreseeing the

importance his trip to India would have for his life and work. It was

there that he would meet Marie-José, his second wife and the love of

his life, and he would undergo a spiritual conversion that inspired,

above all, Viento Entero, [Wind from All Compass Points],

published in 1965, which he described as a poem that explores distinct

realities simultaneously." It begins by saying:

|

El presente es perpetuo Los montes son de hueso y son de nieve Están aquí desde el principio El Viento acaba de nacer |

The present is motionless The mountains are of bone and of snow They have been here since the beginning The wind has just been born

|

(Translation by Paul Blackburn)

Ladera Este and El Mono Gramático also grew out of his sojourn on the Indian subcontinent.

By the time I met Paz on that Mexico City street, he had already composed Piedra de Sol, [Sunstone], the 584-line circular poem that is a lyrical autobiography ending with a colon and the same lines with which it begins. For me, Paz's work is clearly divided into two periods, the Mexican surrealist period, which he collected in Libertad Bajo Palabra, and that of rupture, the break with his own poetic past which had begun in 1962 beginning with the publication in 1962 of Salamandra. He and I had already made contact in 1961, when I sent him my second book, La Tumba de Filidor, or Philidor's Tomb, while he was in Paris, and he replied in a letter full of recognition.

During his time in Paris, the Mexican poet had maintained an extensive friendship with the surrealists André Breton and Benjamin Péret who, he believed , had reconciled poetry with revolution. Nevertheless, years latter Paz wrote an essay criticizing the politically inspired work of the Communist poets Rafael Alberti, César Vallejo and Pablo Neruda. In 1943 Paz had had a falling out with Neruda, then Chile's Consul in Mexico. During a dinner at the Centro Asturiano given in his honor by Mexican intellectuals, Neruda publicly accused Octavio Paz of joining a conspiracy against him and said Paz was wearing a white shirt that was "cleaner than his conscience." Paz recalled later that after a string of insults, " I interrupted him. We were about to come to blows when they separated us and some Spanish refugees jumped on me and hit me. Out on the street I felt beaten and broken, like a humiliated waiter, like a hoarse bell, like an old cloudy mirror."

In 1966, Octavio

Paz, Alí Chumacero, José Emilio Pacheco and I brought out Poesía en

Movimiento, published in England and the United States as New Poetry

of Mexico , an anthology spanning 1915 through 1966. I still have

the letters Octavio sent me from India analyzing the work of several

Mexican poets. In his prologue Paz alluded to the criteria which

governed our choices, stating that "At one moment in the discussion the

real difference came up: Alí Chumacero and José Emilio Pacheco

maintained that, on the side of the central criteria of change, we

should take into account other values: aesthetic dignity, decorum ---in

the Horatian sense of the word---perfection. Aridjis and I were

opposed. It seemed to us that to accept this proposition was to fall

back into the eclecticism that for many years dominated the criticism

and literary life in Mexico. We did not convince them, nor did they

convince us... Not withstanding our wish for a partisan book, Aridjis

and I were swayed, unhappily." The book was originally intended for the

Fondo de Cultura Economica but with the ousting of Armando Orfila

Reynal from the government-owned company (which he had made into a

great publishing house) in punishment for having published Oscar Lewi's

groundbreaking The Children of Sánchez, Poesía en Movimiento

became one of the firsts books brought out by the new house which

Orfila founded, Siglo XXI Editores, and has already gone through 36

printings.

In 1966, Octavio

Paz, Alí Chumacero, José Emilio Pacheco and I brought out Poesía en

Movimiento, published in England and the United States as New Poetry

of Mexico , an anthology spanning 1915 through 1966. I still have

the letters Octavio sent me from India analyzing the work of several

Mexican poets. In his prologue Paz alluded to the criteria which

governed our choices, stating that "At one moment in the discussion the

real difference came up: Alí Chumacero and José Emilio Pacheco

maintained that, on the side of the central criteria of change, we

should take into account other values: aesthetic dignity, decorum ---in

the Horatian sense of the word---perfection. Aridjis and I were

opposed. It seemed to us that to accept this proposition was to fall

back into the eclecticism that for many years dominated the criticism

and literary life in Mexico. We did not convince them, nor did they

convince us... Not withstanding our wish for a partisan book, Aridjis

and I were swayed, unhappily." The book was originally intended for the

Fondo de Cultura Economica but with the ousting of Armando Orfila

Reynal from the government-owned company (which he had made into a

great publishing house) in punishment for having published Oscar Lewi's

groundbreaking The Children of Sánchez, Poesía en Movimiento

became one of the firsts books brought out by the new house which

Orfila founded, Siglo XXI Editores, and has already gone through 36

printings.

The next time I saw Octavio was in July 1967 during the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy, where I met Marie-José for the first time. During the poetry evenings we read alongside Giuseppe Ungaretti, Allen Ginsberg, Stephen Spender, Ingeborg Bachman, Charles Tomlinson, John Berryman and Rafeael Alberti. In the intermission of performance of Don Giovanni, with sets by Henry Moore, we had a strange encounter in the coffee bar with Ezra Pound. Paz, Ginsberg and Tomlinson have already given their versions, but I have yet to write mine. One night after his reading and the applause Ginsberg was carried off to jail by the Italian carabinieri, for having used the words "jack off" in public. Octavio Paz, at the time Mexico's Ambassador to India, and I, discovered he was gone and set off to rescue him, for none of the other poets or the festival organizers had noticed his arrest. When he was released, Allen Ginsberg emerged with a grin on his face, claiming head won a victory for poetry.

Octavio Paz returned to India, but fourteen months later he resigned his post to protest the violent methods the Mexican government used against the student movement. The repression culminated in the October 2, 1968 massacre in Tlatelolco at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas ---The Square of Three Cultures---, where hundreds were killed, supposedly on orders from President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. Paz announced his resignation a few days before the opening of the Olympic Games in Mexico City.

Octavio

and Marie-José spent

several semesters at universities in the United States and England,

including Cambridge and Harvard. Wherever I met him. he was always in

the company of poets, for until the day of his death he was in touch by

telephone or through the mail (he was a great letter writer) with poets

all over the world.

Octavio

and Marie-José spent

several semesters at universities in the United States and England,

including Cambridge and Harvard. Wherever I met him. he was always in

the company of poets, for until the day of his death he was in touch by

telephone or through the mail (he was a great letter writer) with poets

all over the world.

Upon his return to Mexico, he founded the literary magazine Plural. He left the magazine after the government of President Luis Echeverría mounted a coup against Julio Scherer García, the editor in chief of Excélsior newspaper, which had sponsored the magazine, and founded a new magazine called Vuelta. For the greater part of the Cold War years, always going against the grain of the Latin American left, Octavio Paz voiced his opposition to the former Soviet Union and to Fidel Castro's Cuba. In the 80's, after a speech given in Frankfurt (where he received the Publishers' Prize) at the International Book Fair criticizing the Sandinista government in Nicaragua, the Mexican left believed the poet was calling for a North American invasion of the Central American country. There were demonstrations against him in front of his Mexico City near the US Embassy, and he was burned in effigy.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the Mexican writer was proud of having predicted the collapse of the communist world in his essay "El imperio totalitario" "The Totalitarian Empire" in which he had written "The solidity of the Soviet Union is deceptive: the true name of this solidity is immobility. Russia cannot move; if it moves it will crush its neighbor-or collapse inward on itself."

In 1983, Paz and I met at the wake of Luis Buñuel. He was profoundly moved and his eyes ran with tears as the funeral staff carried away the coffin of the Spanish filmmaker. In 1950, as an official of the Mexican Embassy in Paris, Octavio Paz had taken Buñuel's film Los Olvidados to the Cannes Film Festival and handed out an article he had written about it in the lobby, even though the Mexican Ambassador and establishment writer Jaime Torres Bodet, felt the film dishonored his country and opposed its screening at Cannes. The film won the prize for best director.

Towards the end of December 1996, a fire in his home that burned works of art, books and cats forced Octavio Paz to move with his wife to a hotel in Mexico City. The following July he went into the hospital for cancer treatment. On November 11, 1997 and international news agency reported Octavio Paz's death, sparking a darkly humorous phone call from the author, bedridden with bone cancer, to a local television station. He said, "the art of dying is the art of playing hide and seek, but you have to know how to play this art, which is the most delicate of all... and difficult." Shortly afterwards my wife Betty and I visited Octavio and Marie-Jose in the spacious colonial mansion on Francisco Sosa Street in Coyoacán which was to be his final abode. Though his body was riddled with cancer and his face gaunt, Octavio's mind was a sharp as ever, and we were astonished by his mental sense of urgency which sought to steer the conversation away from what he viewed as trivia to deeper subjects, and his impatience to hear news of mutual friends we had recently seen in the United States and Europe, such as Yves Bonnefoy, Lasse Soderberg and W.S. Merwin and he kept anxiously asking "What else? What else?"

On December 17, 1997, during the official inaugural ceremony for the Octavio Paz Foundation, there appeared in a wheelchair a man sunken into his own body, with an aged face and trembling hands. There, Paz affirmed, gesturing skyward, "Mexico is a solar country --but it is also a black country, a dark country. This duality of Mexico has preoccupied me since I was a child." Afterwards, a few close friends joined him in his room for a private visit, and the name of the Rumanian writer E.M. Cioran came up. Paz quickly fell to dissecting Cioran's life and works, beginning with praise and ending with censure of Cioran's fascist tendencies in Rumania before he moved to France.

After thirty-four years of shared happiness during which they never spent a day apart, Paz died in the arms of Marie-José, his mind clear to the very end. Thirteen years earlier, when he learned of the death in Paris of Argentine writer Julio Cortázar, who was also born 1914, Paz had remarked, "We are never ripe for death."

I would

like to read a poem I dedicated to Octavio in the 1970's. First I will

read it in Spanish , and then (in a translation by Eliot Weinberger).

|

EL POEMA El poema gira sobre la cabeza de un hombre en círculos ya próximos ya alejados El hombre al descubrirlo trata de poseerlo pero el poema desaparece Con lo que el hombre puede asir hace el poema Lo que se le escapa pertenece a los hombres futuros. |

THE POEM The poem spins over the head of a man in circles close now far The man discovers it tries to posses it but the poem disappears The man makes his poem from whatever he can grasp That which escapes will belong to future men |